Are you ready for some filmed football?

These days, America has football on the brain, but there was a time when the country needed to be schooled. Nope, it wasn’t always America’s Game; something this visual needed vision.

In the early 1960s, NFL Films, a small but ambitious company based in South Jersey, helped capture the poetry, magic, and primal urge of professional football. Try Morse-coding these themes with a movie camera: Violence, grace, frustration, anguish, and heroism. Add in stirring copy that equaled that of Ulysses, and an orchestrated score as rousing as a Wagner concert.

The sport eventually grew and ingratiated itself into the culture, thanks to the long pass thrown by NFL Films. The media took notes and took notice, from ABC Sports (“the thrill of victory to the agony of defeat”) to ESPN and beyond.

The company has since been largely eclipsed in the digital age, but surprisingly it is still around and still strongly contributing to the sport (and to the visual arts). The films of its archives remain a wonder to behold, vintage or no.

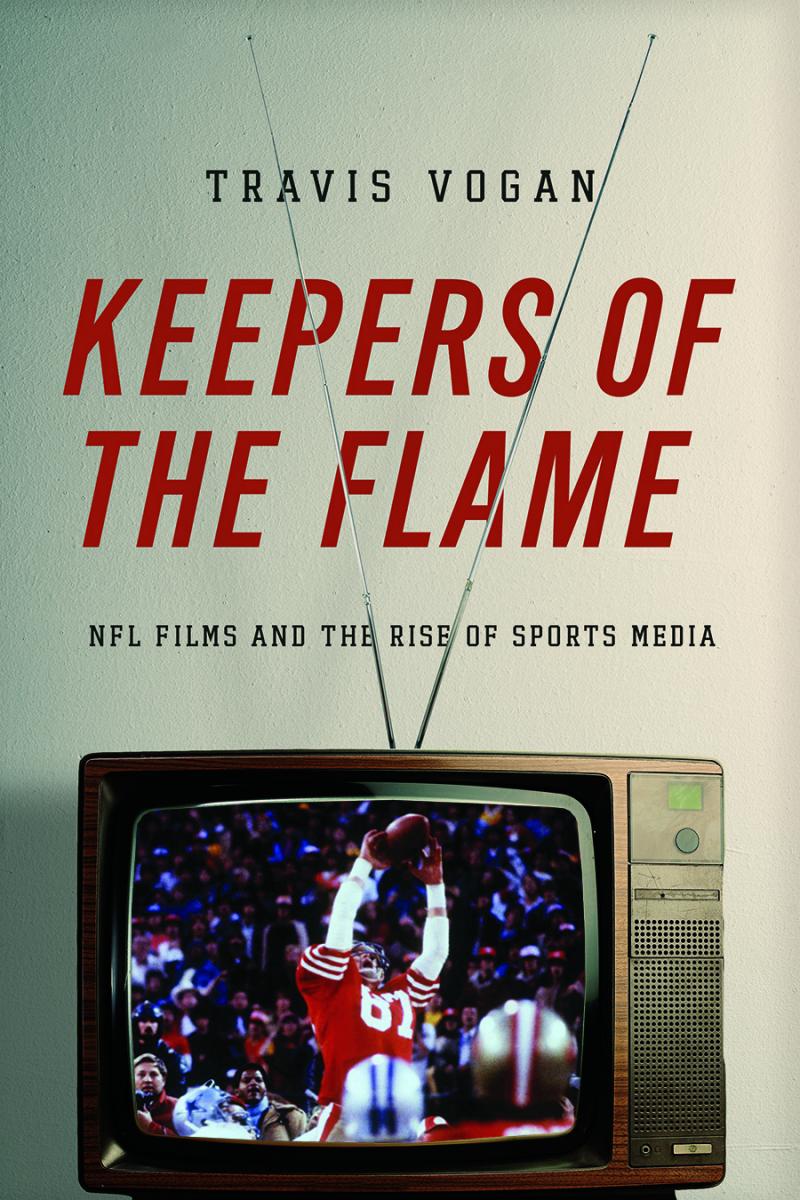

Travis Vogan, University of Iowa assistant professor of journalism and mass communications and American Studies, unwinds the remarkable story in his amazing book, Keepers of the Flame: NFL Films and the Rise of Sports Media.

Here, he calls the play:

What turned on the inspiration for a book about NFL Films?

NFL Films is an interesting case of an independent film company that wanted to be a part of this huge corporate machine.

Its documentaries themselves are just so distinctive within sports media and even within documentary filmmaking. The story behind it I think is equally fascinating.

When NFL Films got going in the early ‘60s, how did America feel about football?

Some people say it was the third most popular sport after baseball and college football. In any case, it certainly wasn’t the most popular sport. It didn’t have the aura that it has now.

Now, it’s a huge part of our everyday lives. Even if people don’t care about football at all, they are going to watch The Super Bowl.

I wouldn’t say that it was a fringe sport by any stretch, but it wasn’t the iconic organization that it is today. A lot of that had to do with its marketing infrastructure that romanticized the game. That exceeds what happens on the field, transforming itself into what is now called America’s Game.

The company was started by Ed Sabol and his son, Steve. Tell us about the beautiful writing of Steve Sabol, whose scripts are heard in these early films.

He said he was influenced by Ernest Hemingway, Rudyard Kipling and even Gertrude Stein. He really saw himself as an epic poet in certain ways. But the scripts were also marked by a degree of brevity. He said that words are like medicine; an overdose can kill you. He was a real quotable guy. He would help his subject reach a mythic status.

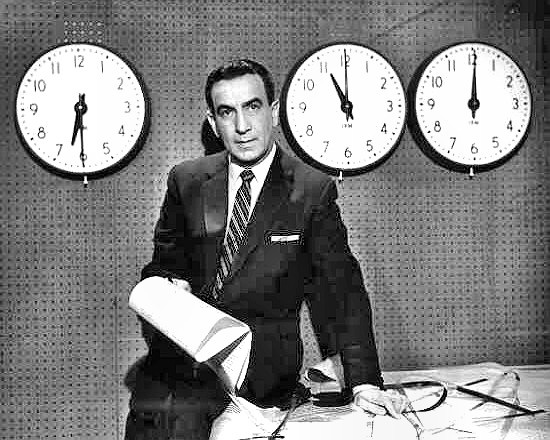

John Facenda was the grand old man of Philadelphia’s local news broadcasts. How did he hook up with and become the voice of NFL Films?

He was a Philadelphia local and Ed Sabol was a man about town and knew a lot of people. He was a salesman and quite a gregarious sort. He asked Facenda if he would be interested in doing some narration, and Facenda was really enthusiastic about the idea.

The funny thing about it is that Facenda didn’t know much about football. He wasn’t really a fan, necessarily. He may have liked the game, but he was not the expert you might assume. And yet his voice is so closely associated with the game. He would write in the margins of the script operatic terms like basso profondo and allegro to give himself cues as to how he would read these scripts.

How did NFL Films influence video technology?

NFL Films pioneered a lot of practices that are now commonplace in sports television. They shot on film and saw themselves as rooted in film.

The practices they used influenced how television showcased the game: multiple cameras, ground-level slow motion, reverse angle replay, soundtracks obviously. Also, on-field sound, which was huge. They are still the only organization that can mike players and can bring microphones into the locker room.

How did it slowly begin to fade from the scene?

NFL Films created the conditions for its own obsolescence. You can say that it was a victim of its own success. Earlier on, in the early ‘60s, when NFL Films was just getting going, its programs like NFL Game of the Week and This Week in Pro Football were some of the only ways you can see football outside of live broadcasts. You can connect that to ESPN and cable sports in general.

Highlights were soon an important part of the game, making NFL Films less relevant. It also created a media landscape that focused on updates and scores and highlights and injury reports.

NFL Films didn’t become extinct by any stretch, but they faded into a particular niche. In fact, a lot of the stuff NFL Films does now is to fuel the NFL Network, an organization that kind of grows out of ESPN and is providing updates and briefs.

When exactly did NFL Films get left behind?

We can trace it to the beginnings of cable TV in the early 1980s.

NFL Films used to do the Monday Night Football halftime highlights, which was huge. These were things that people would really look forward to.

ABC at the time was the leader in sports television. With cable, the highlights were happening immediately after the game, so the halftime highlights of games that happened the day before became less relevant. The outlets buying this type of programming shifted their focus more to the immediate.

The thing that really marked the beginning of this decline is when the NFL started its own network, NFL Media. It was trying to do its own version of NFL Films.

I wouldn’t say that NFL Films is obsolete or was cast aside entirely, but it is now providing more niche programming within the NFL Network rather than being the NFL’s signature media product. It’s now part of a much larger media infrastructure. It’s not the network’s focus. But there would be no NFL Network without NFL Films.

What surprised you most about your research for the book?

I was really surprised at how accessible [the NFL Films archive library was]. Steve Sobol gave me an open invitation to visit. I thought it would be a little bit more Hollywood or a little bit more corporate.

There was a strange, idiosyncratic process to their archives. One of the things they’ll do with their digital cataloging system is to archive things not only according to the date, when it took place, the people who were present, and the teams, but they also archive it in terms of “hands in the mud,” or “mud,” or “cleats in the dirt,” or “sweat dripping.”

They also categorize the films according to the impact they think they will eventually have on viewers. A big thing NFL Films does is try to move the audience, try to give the viewer goose bumps. So they would archive certain footage according to “good” to “very good” to “Oh, God!” in terms of emotional impact.

These are really odd ways to categorize footage, but they make sense within the aesthetic world in which NFL Films operates. To me, it was mind blowing. Incidentally, it’s the largest sports film archive in the world.

Dig this perfect musical example:

Buy Travis’ book here, and find out more about NFL Films.