How The Mary Tyler Moore Show made it after all

When CBS broadcast the final episode of The Mary Tyler Moore Show on March 19, 1977, the entire world came to a stop to watch it.

These days, series finales are commonplace, but when Mary told the world that her uber-successful series had an expiration date, the news was stunning, and met with universal grief.

The smart logic: quit while you’re ahead. Go out on top. We didn’t understand it then. We didn’t want to understand it. We wanted The Mary Tyler Moore Show to go on forever. But we understand now. Perfectly.

Seven years before, it would have been difficult to see the Emmys, the high ratings and the adulation the series would eventually earn.

The Mary Tyler Moore Show quietly broke boundaries and, unlike most sitcoms that were on the prime-time schedule in 1970, was actually funny. It was so good, it was almost too good. It almost never made it to the air.

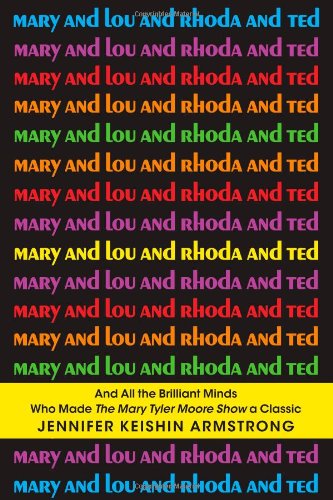

In her feel-good book, Mary & Lou & Rhoda & Ted, author Jennifer Armstrong describes how a groundbreaking show almost missed its green light from wussy TV executives, and how lightning struck for its cast, crew and generations of viewers.

In her feel-good book, Mary & Lou & Rhoda & Ted, author Jennifer Armstrong describes how a groundbreaking show almost missed its green light from wussy TV executives, and how lightning struck for its cast, crew and generations of viewers.

Originally, the idea of a single woman at age 30, who put career ahead of marriage and family, was considered tragic, not comic. By 1977, nobody even blinked at the concept, except to blink back tears that a show this good was about to bite the dust.

Here, Jennifer describes for us the fascinating show behind the show.

In 1970, the idea of a smart, single career woman who was not a merry widow and not wacky and infantile like Lucille Ball was a hard sell to network executives.

When the creators of the show, Jim Burns and Allen Brooks, go to pitch the show, their first idea was that Mary was divorced. It was something that was not seen on TV yet. The women on TV [in 1970] are married housewives. The network wanted nothing to do with a divorced woman.

Everybody wanted to do “Lucy” for good reason. It had been going on for twenty years: wacky mishaps. [The Mary Tyler Moore Show] was a completely foreign idea to them.

So Burns and Brooks compromise, but just a bit.

They had given up on the divorce idea. Instead, [Mary Richards] was putting this guy through med school, but they never really tell you if she was living with this guy or not. It’s all very vague and that’s why it’s vague.

The show gets on the air in the fall of 1970, but it does not get the love it deserves right away.

The pilot was very strong and the critics still didn’t get it. The critics didn’t understand what they were seeing at first. They didn’t like the idea that she was single. That was baffling to them: she’s such a loser because she’s still single at her old age of 30. They didn’t like that [Mary’s friend and neighbor] Rhoda was too abrasive. They didn’t get what would later become the best parts of the show.

Once the show catches on, it inspires endless copycat attempts. But most of these series suck.

It happens over and over again in Hollywood. Everybody rushes to try to mimic a successful formula. Part of the The Mary Tyler Moore Show’s success was because it was something new, and also because a lot of women strongly related to the single working woman.

Yet ultimately that was not where the magic actually lay. Just to mimic the basic setup [a single working woman and her friends and co-workers] is not going to give you a hit show.

You can have a single girl all you want, but if you don’t have the amazingness of a Valerie Harper and Cloris Leachman and Ed Asner and Ted Knight, it’s never going to be the same.

Part of that magic was the fact that Mary and her real-life husband/co-producer, Grant Tinker, had a real respect for writers and actors.

Tinker had a similar no-nonsense sensibility. It was a great pairing, at least in terms of business. They did that by being very respectful of the artists they hired. It was the place in the industry where creative people wanted to work.

Mary becomes a success, and spawns spinoffs and other hit series like The Bob Newhart Show, which appeal to urban, educated audiences.

They wanted the stories to come naturally from the characters, instead of the other way around. I love Norman Lear shows [All in the Family, Good Times], but [Lear] would throw giant topics of the week onto his characters: “yell about this for 22 minutes.”

[In contrast,] I think Mary would actually ask for pay equal to her male predecessor. It comes really naturally. It’s not the same as the explosive nature with which Norman Lear shows operated.

Mary announced the show’s eventual finale while it was at the top of the ratings and a critical darling.

It was one of the first shows to announce its own demise. “We’ve decided to end the show two seasons from now. We are telling you, the public, now.”

That would be something difficult for even a Lost to pull off. But they just decided that they wanted to have their own end date, and they were able to work toward that and give us a big finale.

One of the reasons for the show’s green light in 1970 was that women’s liberation was a hot topic.

It was one of the inspirations behind me looking into the show. They had more women writers than any previous show, who were able to bring their own experiences.

There was a market for these new, young liberated ladies. That was a huge driving factor, but once that was not hot anymore, it was time for Charlie’s Angels.

Were feminists happy that Mary was on the air?

During its run, feminists were not super excited about it. When your show becomes emblematic of a group, it comes in for a lot of criticism, because they want it to be everything.

They wanted Mary to be the perfect feminist, which is not a realistic idea for any human being. Their biggest gripe was her continuing to call her boss Mr. Grant when everybody else called him Lou.

The writers for the show insisted that this is a character trait that Mary would have, and therefore, she is going to keep it.

Yet today, Mary is seen as that proto-feminist.

Through the next few generations, and through reruns and Nick at Nite and DVDs, Mary Richards has become this retrograde feminist icon. We all embraced her as this perfect person that we can relate to but still feel empowered by.

Read Jennifer’s awesome book here. It will truly make you feel good.

Watch one of the best single episodes of any situation comedy ever. Then you’ll understand: “Chuckles Bites The Dust.”