A new John Wayne biography separates the man from the icon – and the cliche.

Even though old soldiers never die, John Wayne won’t fade. Decades after his death, he resonates and arouses emotions, opinions, and iconography. He’s still what many people think of when they think of America.

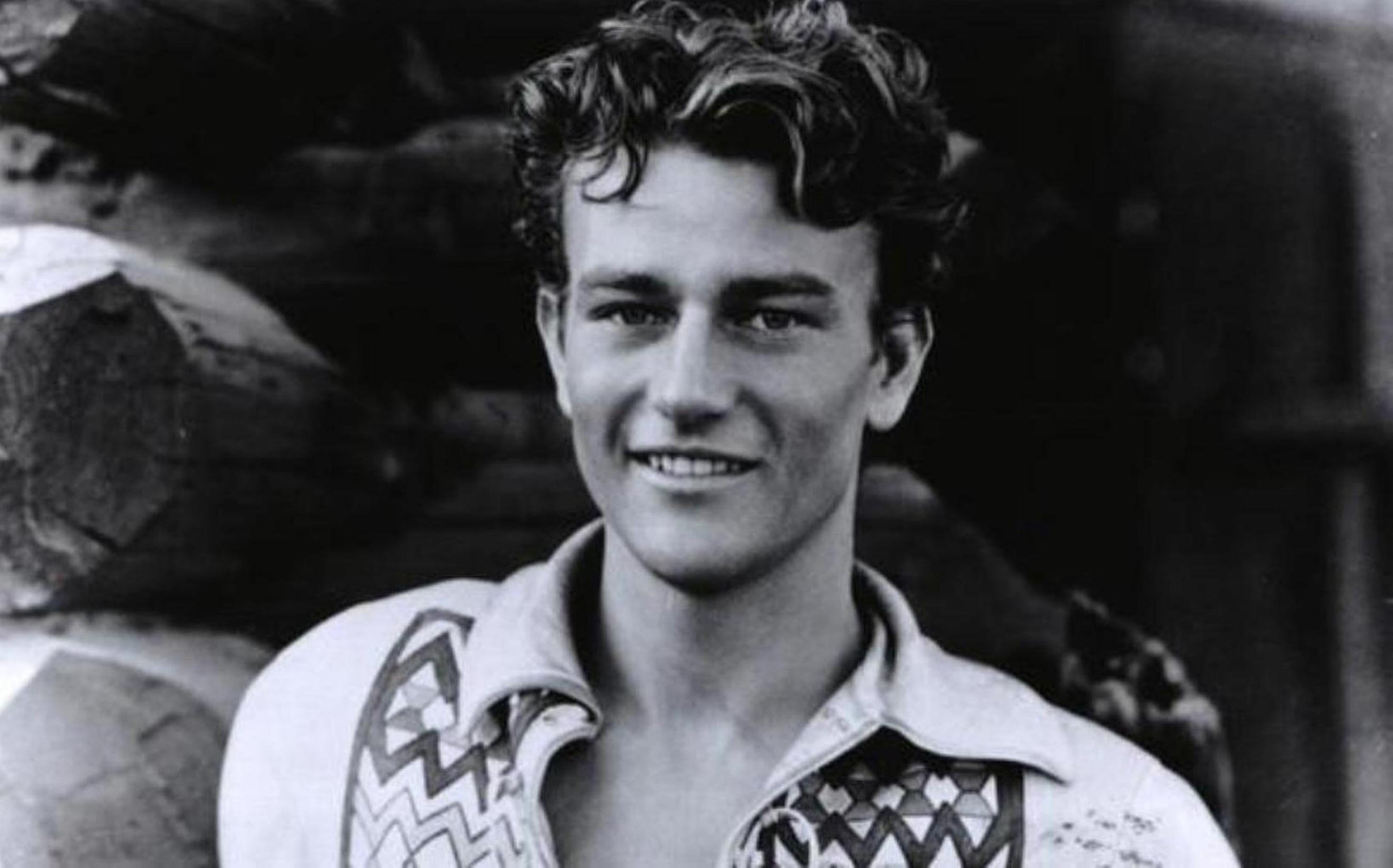

He was born into nothing in the middle of nowhere, with the girl’s name of Marion Morrison. The young actor was impoverished, but also as charismatic as all get out. He quickly found a niche in the burgeoning film business, depicting the very definition of steadfast masculinity. Cowboy, soldier, cop, it didn’t matter, as long as he was putting out product and being John Wayne. It was a rush and a highly addictive fix, especially for male moviegoers. He was a top-ten box office draw every year for 26 years.

His politics, to say the least, were to the right of Ronald Reagan. His conservative loyalty led him to support the McCarthy hearings and the Viet Nam war. He made like-minded friends and resentful enemies, but his popularity continued to charge like a mad horse.

When times changed and a new generation swooped into Hollywood, Wayne became an anachronism to everyone except The Silent Majority. To some, he was a joke, a character to spoof and dismiss. To others, he represented what was best about America, masculinity and morality. Everyone had an opinion on him, one way or the other.

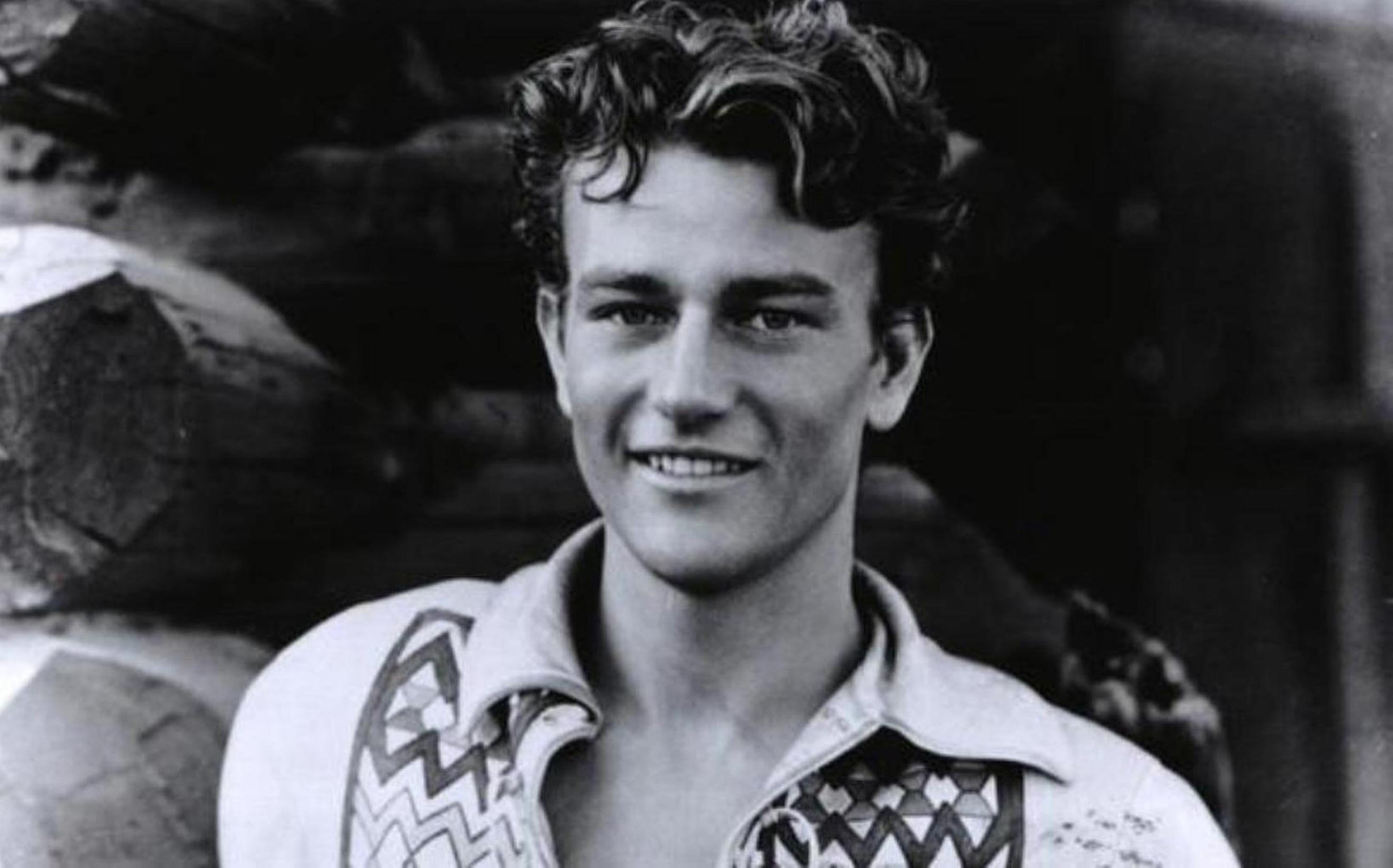

Scott Eyman’s new biography peels back the layers to show the man himself, separating out the myths and the misunderstandings, and filtering out the noise.

Here, he gives us a preview and helps us get a grip on the man who, even in death, is bigger than life.

What is it about John Wayne, even after all these years since his passing?

There was something about Wayne that compelled attention. Your eye went to him. He seemed to be carrying huge emotional and spiritual weight as an actor in terms of what he could convey to an audience: The sadness, the longing, the grief that he could carry. And that appealed to me.

He seemed to be universally loved at first, and then as times changed he came to be despised by a younger generation. How did this happen?

He seemed to be universally loved at first, and then as times changed he came to be despised by a younger generation. How did this happen?

The way he was treated was basically because of politics, which I’m not going to defend. To coin a phrase, you don’t throw the baby out with the bathwater. There was a lot more to him than just reactionary politics.

You have special insight into the man because you spent some time with him.

I met him in 1972 for 90 minutes, and the guy I met I could not find in any of the books that were written about him. I was 21-years old and he would have been 65. He was extraordinarily gentlemanly and courteous to a kid with no credentials. He gave thoughtful answers to my questions. He wasn’t used to getting those kinds of questions because at that point, everybody was bating him, about Viet Nam, Richard Nixon, and he could not not respond. He had to respond. They would just wave a red flag and the bull would charge.

Would you consider him a good actor?

I think he’s a very good actor. He had a much wider range [than most people perceive]. He’s not a chameleon actor. There are very few chameleon actors, I mean, really. A Daniel Day Lewis comes along once every 50 years. And a guy like Daniel Day Lewis comes along because he doesn’t have a specific identity of his own. Wayne had a personality, but he could do a lot of interesting variations on that personality. He was an excellent screen actor.

We’re all very familiar with the legend and the cliches, but what was he like as an actual human being?

If I hadn’t met him, I would have been much more surprised by the depth of his reading, by his taste for decorating houses, his pleasure in buying clothes for women friends. Things like that would have surprised me a lot.

As an actor on screen, his body language is very expansive and theatrical. He’s big with the shoulders. He throws his arms out. He has big, broad gestures. As a man, he would hold himself very quietly. I began to realize that John Wayne the actor was not the same person as Duke Morrison. I realized when I started the book that I was in for some surprises.

He had a certain degree of self-awareness, but not about women. He was pretty naïve about women. He was a bad judge of character. He was a poor businessman. He wanted to be in business with his friends, and that‘s the worst thing you could possibly do. So he had nowhere near the amount of money that he should have had, considering the amounts that he earned. A lot of his investments went south. So he had his failings and flaws, but they were a function of emotional generosity rather than narrowness or being closed off.

As times changed, John Wayne made attempts to keep up, yet it was too little and too late.

A couple years before Clint Eastwood did Dirty Harry, Wayne turned down an earlier draft of the script. He turned down a lot of things. He turned down All The King’s Men, Patton. He didn’t worry about it, but he regretted turning down Dirty Harry, because he sensed that Eastwood had something new. And the film lifted Eastwood to a different level than he had been on before.

Wayne needed to do something to stay current, so he did McQ. It’s all right. It’s not great. He’s too old, basically. If he had done it ten years earlier, it probably would have been a lot better. His timing was off, which happens.

Increasingly, I think he was hemmed in by his own allegiance to his own iconography. He was in the John Wayne business. He would leave his comfort zone for [film directors and collaborators] John Ford or Howard Hawkes. He would do what they told him to do. He liked any strong, masculine, authoritarian director. He was a passive guy and did what he was told. But when he was producing his own pictures, he tended to be the big man on campus. He set the parameters, and he wanted to do what I call “comfort westerns,” projects that he knew would please his preexisting audience but wouldn’t broaden the audience out.

His 1968 film, The Green Berets, was pro-Viet Nam war and a monster hit. Yet it caused a huge rift with the moviegoing public, especially among the young of The New Hollywood.

That movie was like throwing down a gauntlet to the Left and the antiwar movement. By the time the movie came out, the streets were filled with rioters. And you also had Nixon getting elected and appealing to the Silent Majority, which was culturally conservative and supporters of the military and our actions in Viet Nam.

At the Oscars ceremonies in 1979, he handed out the award for Best Picture, The Deer Hunter, which was a starkly different take on the Viet Nam war than The Green Berets. He was dying from cancer at that time, but the irony of the moment shows a cultural torch being passed.

He outlasted the events of the Viet Nam era. Everybody knew he was extremely ill. When you saw him [at that Oscar telecast], there was no question that he was dying. He had already achieved that level of grand eminence. He transcended the politics of the Sixties by that time.

Since his death, John Wayne has found a new audience and a new respect.

It’s like a torch being passed. People watched John Wayne with their fathers and their grandfathers and they associate John Wayne with that experience. And they’ll pass it on to their kids.

I had no concept of this underground [audience] out there. Not everybody shares his politics by any means, but a lot of these people just love him, and they love his acting and they love the way he looked. He just speaks to people on a very emotional and psychological level.

I figured I was the only guy among my friends who went to see John Wayne movies. I figured there would not be anybody buying this book. I was wrong.

Watch this touching scene from an earlier Oscars telecast:

Question:

Did John Wayne’s politics make you more of a fan or less of a fan? Or did it not matter to you at all? Scroll down to the comments area to share your thoughts!

3 Comments