Architects and retail merchandisers form an unlikely alliance. The result: the modern mall.

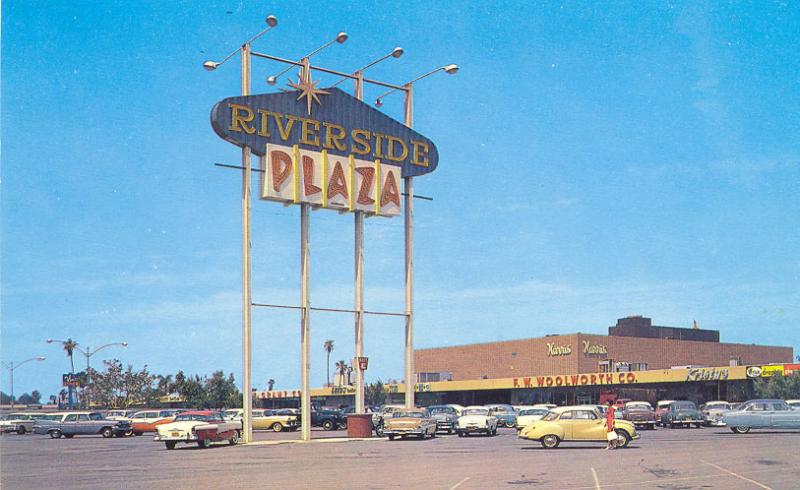

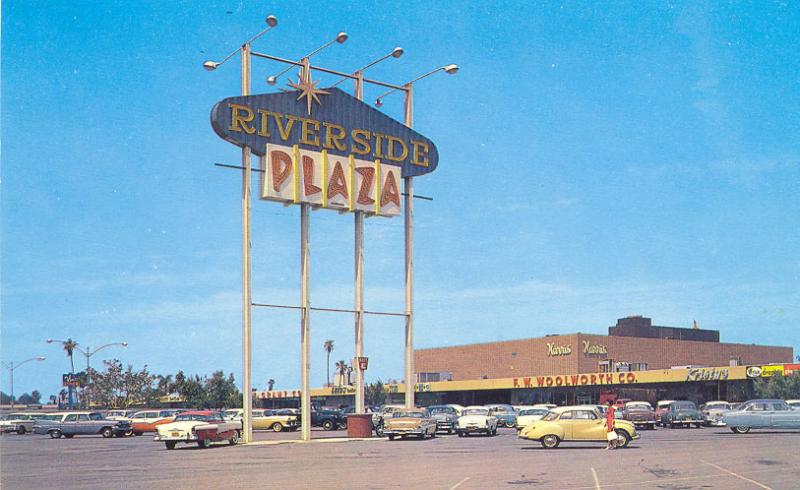

In postwar America, the suburban mall was a welcome, convenient spectacle and second home. It was also an important cultural touchstone, but ask any architect at the time about its design merits and you would get two big, ugly thumbs down.

These days, with malls in definite decline, hearts have softened and appreciation has heightened. Heads have turned back to see the mall as a beautiful coming together of planning, capitalism and aesthetics. What we see in the rear view mirror is a triumph of modernism.

David Smiley, a teacher at the Graduate School of Architecture, Planning, and Preservation at Columbia University, captures and dissects this unusual story in his book, Pedestrian Modern. Here we learn of the motives behind the open-spaced, outdoor mall, and how it was a reaction against 19th century urban planning while dedicated to being decidedly pro-pedestrian (an astounding concept at the time).

Here, he gives us a reserved parking spot so that we can get a better view of how malls went modern. Dig:

How did you decide to write a book about modernism through the study of malls?

In some ways, you can say that it’s a book about the history of modernism in America using the vehicle of shopping as a lens. It’s a book about malls, but in fact, it’s a book about modernism.

When you go back to early retailing, I was seeing architects studying modern architecture and doing retail work that they thought of as a modern idea. They saw it as a good combination. The magazines supported it. Here’s a perfect demonstration of the rational principles of retailing and the rational principles of modernity.

The architects’ challenges were basically everything that was important in 20th century life: commerce, cars and suburban planning.

To them, the parallel thread is that the automobile and suburbanization and the changing American city required adjustments, including shopping. Even before the war, there were a lot of different ways of thinking about community organization, not just shopping, with the car as secondary.

Architects saw themselves as doing modernist work, doing rational planning. They wanted to address big problems [the entire community], not just individual buildings.

Define urban modernism.

I can tell you what it became, and how it became a large-scale, massive replacement of the city. In some ways, it was forced into that shape.

In the 30s and the 40s, even earlier, it wasn’t just the architects; it was also urban planners and real estate developers. They saw the 19th century fabric as utterly inefficient, even unhealthy, and not attuned to 20th century ways of life. They needed to figure out a new scale, new ways that things should work. And the blocks and the lots, which was the typical urban scale, were no longer working.

The early shopping centers realized that they needed to get beyond the strip. Those were old real estate models, old architectural models. They needed to create a new land scale, or property scale that was a bigger plot of land so that there was more flexibility to study building mass, parking, servicing, sidewalks and such things.

The modernism in early shopping centers is similar to other areas of architecture where they saw they needed to overcome the 19th century fabric.

You also address the right of the pedestrian, That must have been an astounding concept at the time, since the car was king.

That became a mantra for the challenge to the old-fashioned city. The old-fashioned city was overrun by automobiles and trucks, and architects weren’t going to deny the importance of that, but they needed to reverse the argument and say, “let’s figure out how pedestrians can be designed for as the primary concern,” and everything else should follow through that. This idea of pushing the automobile out of the center was not so much a rejection of the automobile, but a new set of priorities.

The Cold War, protecting American citizens against a possible atomic attack from The Soviet Union, was also a huge concern and consideration when designing malls.

Some [planners] very boldly said that malls were fallout shelters and points of rescue. But I’m still unsure about how deep that entered into real policymaking. It’s a historian’s dilemma. It disappeared for a while and then came back. But the fact is that it was part of something that proceeded the Cold War, what they called the regionalization of the city, or the city as a regional constellation.

That meshed very nicely with Cold War rhetoric. It was the idea of making the city more of a series of sub-cities, less dense and less unhealthy. In the early Fifties, the historical emergence of ideas of dispersed cities meshed very nicely with Cold War politics. The Cold War, in this case, added to already existing trends and gave them a new life.

Why did you end the story in 1956?

That’s when Southdale Center [Edina, MN] opened, the first enclosed mall. That was the culmination of what I would call modernist control: the idea that you can create a complete, new environment cut off from the world, fully controlled, fully rationalized. That’s the end of a story as well as the beginning of another story. If I had gone further, I wouldn’t have known where to stop.

Malls are experiencing tough times these days. What are some of the reasons that may surprise us as to why?

The pace of regional change has increased. In the ’50s and the ’60s, you could expect a mall to go for ten or twenty years. That was the economic formula. Now, that is just out the window. A mall going ten years now without a major overhaul is considered remarkable.

There are so many kinds of retailing and so many kinds of interests that get served so quickly [now]. The dead mall problem ties into the problem of real estate investment and the way it is organized so that the investments are short term. One year, there is a hot community, but ten years later, it’s lower down the ladder. Malls move further out into the suburbs, leaving an empty shell.

Now, with a return to the cities, some of these malls are actually valuable again, but not in the same way. They turn into libraries or government centers or community colleges. What’s happening to dead malls is happening because they are much more diverse.

Those vintage malls are now getting a new appreciation and respect from the very profession that may have scorned them back in the day.

Some of the very early malls, and even some in the ’60s and ’70s were done by very respected architects. There is much more receptivity among historians now to look at everything and be less judgmental. Unfortunately, some of those early malls are gone. They were gutted and redone, like Roosevelt Field [Long Island, NY]. Historians are realizing that these were important places in American social life.

Buy David’s book here.