One flew over this cuckoo’s nest.

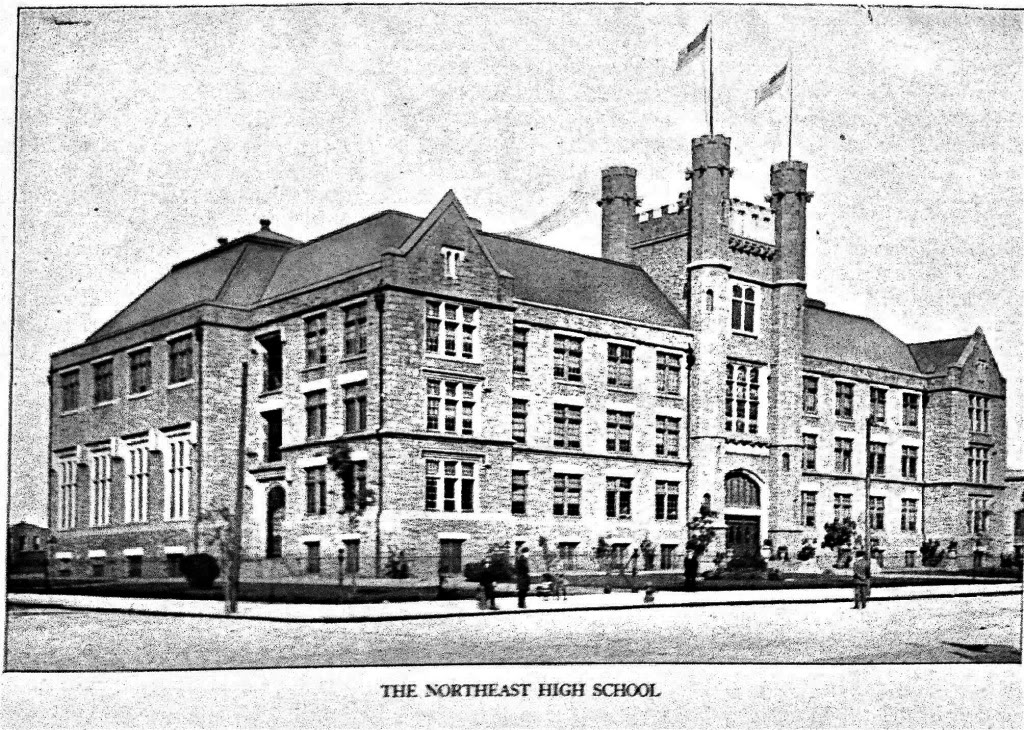

Photographer and author John Webster has helped pioneer an adventure now popularly called urban exploration. In his hometown of Philadelphia, the pickings are easy: exploring abandoned buildings, factories, hospitals, and any structure still standing but not in use.

However, urban adventurers have found plenty of uses for these properties, to be sure. Eerie photographs that go viral, spooky fears and ghosts confronted in the dark night, and, of course, wild parties.

For years, an urban adventure must-see was one of Philadelphia’s most notorious and embarrassing shames: The State Hospital at Byberry.

For years, an urban adventure must-see was one of Philadelphia’s most notorious and embarrassing shames: The State Hospital at Byberry.

Just the thought of it makes many Philadelphians’ toes curl up (but makes urban adventurers’ spidey senses tingle): a corrupt, overcrowded mental hospital lousy with abuse, neglect, immoral drug experiments on patients and even murder.

For decades, Byberry thrived due to political favors, while misery, filth and rape became commonplace. And the property took a long time to die. Years later, skeletons were found in the overgrown weeds.

John captures it all in his new book, The Philadelphia State Hospital at Byberry: A History of Misery and Medicine. Filled with historical photos and eye-opening accounts of misconduct and mismanagement, the book serves as a lesson of the unfortunate results of ignorance, greed, bureaucracy, tied hands and looking the other way.

How did you become compelled to explore an abandoned psychiatric hospital with a corrupt past?

When I first started, I didn’t know anything about it except that it was a mental hospital. It was a whole new experience to me. Today, people call it urban exploration.

When I first started, I didn’t know anything about it except that it was a mental hospital. It was a whole new experience to me. Today, people call it urban exploration.

I became engulfed by this place. I’ve never been in an asylum before. All I was told all my life is that’s where they put crazy people.

It sounds kind of silly, but it’s what got me into history. I didn’t really know anything about history before, and I really didn’t care.

It was a good little personal history lesson, in a way. And the more I learned about it, the more I learned how bad it was, as a stark contrast to some other places. And that intrigued me even more.

The exploration of the abandoned hospital and its grounds (and spooky underground hallways) was shared by hundreds of thrill-seekers, night crawlers, photographers and adventurers over the course of decades.

People managed to get in there and were not scared away. People started to talk to each other about it and it became a party.

What inspired you to write the book?

I couldn’t find a book about it, so I took it upon myself. Everybody I asked had similar responses like, ‘I had an aunt in there;’ ‘I had a friend’s mother who used to work in there.’ Pretty much horrible stories. I’ve never talked to anybody who said, ‘Oh, that place got such a bad rap.’

I couldn’t find a book about it, so I took it upon myself. Everybody I asked had similar responses like, ‘I had an aunt in there;’ ‘I had a friend’s mother who used to work in there.’ Pretty much horrible stories. I’ve never talked to anybody who said, ‘Oh, that place got such a bad rap.’

How did you find the condition of the hospital when you began your own personal exploration?

The place was pretty much in utter destruction when I found it. There weren’t too many areas that were left intact, so it was hard to tell what everything was for.

There was a dentist’s office, which still had a chair in it. That was more interesting because seeing that, the place seemed to make more sense.

The morgue was obviously very intriguing. I’m not a morgue connoisseur, but it was the biggest morgue I’ve ever seen.

Is it true that horrible medical experiments were performed on the patients in the early days?

The Smith Kline French company was in there in the beginning. They tested all kinds of drugs on people in there. It was very harsh because evidentially it was a process of elimination to determine which drugs were effective. If somebody died, they could just do an autopsy and say, ‘ok, we just put a little too much of this in there. Let’s try it again.’

Back then, mental illness and psychological disorders were so misunderstood that you could be committed to the institution for almost anything.

You could be put in there for alcoholism. Even if you had ADHD, you could be in there.

You could be put in there for alcoholism. Even if you had ADHD, you could be in there.

Obviously, this place was bad news. Why did it take so long to shut down?

The shut down process took about three years, from 1987 – 1990. It was the largest state hospital in Pennsylvania. So it had three times the number of patients as any state hospital.

It took them a while to get everybody out. They didn’t try to find homes for everybody. They let a lot of people out on the street. They kept turning up dead or in jail.

The reason that it stood for 16 more years is because there was about $10-15 million worth of asbestos inside of it. They just didn’t have the money to take it out.

So it just sat there, abandoned for years.

So it just sat there, abandoned for years.

That place is prime real estate, but there were political favors done. I’m not sure it went to the highest bidder. I think there was a little bit of bureaucracy going on.

However, this adventure motivated you to explore other abandoned places.

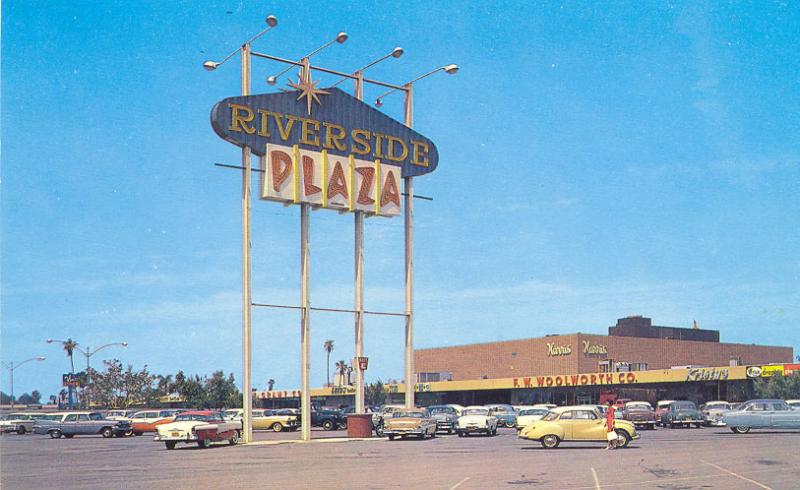

Fortunately, Philadelphia has a lot of historical properties, and unfortunately, a lot of them are not in use. The economy here is not the best.

Power plants, built along the river back in the 1920s, are like castles. They never foresaw a day that they wouldn’t be in use. They built them so permanently. They were so big. Now they’re just sitting there. That kind of thing boggles my mind.

They powered about 25% of the city, hundreds of guys every day. These power plants are such fortresses. They don’t look like they should be abandoned. So you get treated to a lot of architectural details that you just don’t see anymore, and engineering that you just don’t see.

The city really doesn’t have the money to do much with these places, so I’m trying to document them while they are still here. They’re like little time capsules. When I go into a place like that, it’s like time has stopped.

Get this incredible book here.