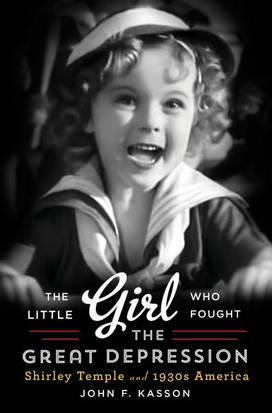

Her winning smile wins hearts and minds during The Depression.

Don’t tell the child: America is in some deep Dustbowl doo-doo during the 1930s. Lack of money, bank closings, zero jobs and no easy answers or solutions meant a possible end to the Republic as we knew it.

Enter Shirley Temple. No Honey Boo Boo this; a child was called to lead a country out of the darkness. Through her films, the golden-haired moppet pumped up confidence, and even helped the economy generate revenue.

On the bummer side, she spawned generations of stage mothers, but here we give Shirley her props as the little girl who kept a downtrodden country chugging until it got back on its dancing feet.

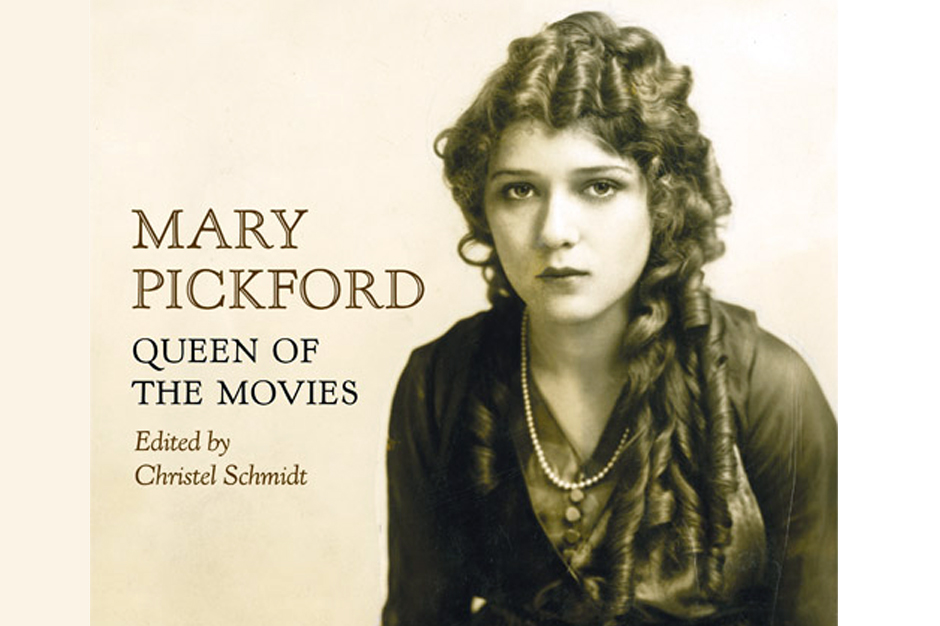

John Kasson chronicles the how’s and the why’s in his book Shirley Temple: The Little Girl Who Fought The Depression. Find out how the little ragamuffin broke the hearts and breezily rebuilt the resolve of the most cynical, disgruntled and hopeless with her winning ways.

Shirl, where are you when we need you, baby girl?

Here, John tells us about the phenom.

Shirley Temple was the perfect storm. Could something similar happen before or since?

This is the period of the golden age of Hollywood and the studio system. Movie attendance goes up in the 1930s. The audience is less segmented than it is today. It was a different market. So Shirley Temple is almost universally seen. Her name recognition is pretty close to 100%. That’s not possible today.

Why Shirley?

She has talent, and other people’s talents bring out her talent. They all work together. A lot of talented people are working with her. Cinematographers, costumers, co-stars are doing their best to bring out what’s in her. And the public responds to her.

She has seventh billing in her first film, Stand Up And Cheer, in 1934. Fox Films does not know quite what to do with her. They lend her out to Paramount for two films while they look for other scripts [for her], and she becomes a bigger star. [Through the rest of the decade], she’s #1 at the box office in The United States and worldwide.

She’s not the prettiest little girl, she’s not the best dancer, she’s not the best singer, but she has a great camera presence, which they exploit. She worked very hard. She worked well with adults and she worked well in front of the camera.

In addition to that, the stories she’s in, which came to be called “Shirley Temples,” are where she radiates hope, trust, and cheer. She’s never going to let anything put her down. She never succumbs to fear or discouragement.

She convinces everyone, especially broken-hearted men and disgruntled grandfatherly figures that if we all just rally together, everything is going to turn out all right.

Can Shirley Temple the actual person be separated out from Shirley Temple the film character?

She is not the same as the little girl in the movies, even though the fan magazines insisted that she was. She was hard-working and teamed with her mother. Her mother is her acting coach and her rehearsal coach. Her mother is the person who is coaching her and urging her on. She’s like a Svengali, and Shirley genuinely seems to like working with her.

One gets the sense that Shirley is more willful and more controlling than she appears in some of her films. She could be bossy, and occasionally rebellious. She was a charming little girl, but she also had an unusual childhood. Most of her playmates were adults. She had two older brothers, but she was the apple of her mother’s eye from the moment she was born. Most of her life revolved around the studio set.

How did America take its cues from Shirley?

First, they go to the movies and respond to her. They take her to their hearts. They want to protect her, adopt her.

In addition, there were Shirley Temple lookalike contests. There were all kinds of licensing agreements. She transforms children’s fashion for girls with the toddler look that she has. There are Shirley Temple dolls, authorized and unauthorized, that become a third of all dolls sold in the 1930s.

She becomes the model child and the model child consumer. She is used by various advertisers and merchandisers to endorse projects and products, and to get people spending again.

All kinds of people, even people who never saw her movies, had pictures of her in their homes, from a black laborer in South Carolina to Andy Warhol’s [childhood] home in Pittsburgh to the offices of J. Edgar Hoover and even Nucky Johnson, the notorious numbers king. He had a picture of her by his bedside.

Anne Frank, in her attic hideaway, she gets out the photos that she’s clipped from fan magazines, and puts them on the wall, trying to make things look more cheerful.

The mania for mothers to have their daughters become the next Shirley Temple must have caused a lot of dysfunction.

Not just stage mothers, but mothers who decide to enter their daughters in Shirley Temple lookalike contests. Some girls liked it and some girls hated it. Shirley Temple was held up to them by their mothers.

That dynamic is, of course, not new. What happens is it becomes filtered into larger ambitions. A child becomes a trophy child, and the parent is pushing the child to do something. It’s more about the parents’ gratification. We have various versions of that today.

Shirley’s first film Stand Up and Cheer {check it out below] is an oddity. Not exactly unwatchable, but strangely put together.

The idea for Stand Up and Cheer was suggested by Will Rogers. Initially, it was kind of a Fox Follies. The title changed in various ways. It was really a revue rather than an integrated plot. Much of it is vaudevillian in structure. Shirley plays part of a father-daughter act.

The premise is that President Roosevelt says that people are paralyzed from fear, and we have to dissolve that rock in the gale of laughter. He appoints a new member to his Cabinet, the Secretary of Amusement. The idea there is that we need people to lighten the load, to cheer up people and get them laughing again.

In a sense, that is just Hollywood self-justification: we need entertainment, and Shirley is part of that plot.The film, among other things, is hitching its wagon to Roosevelt’s star.

A smile is the on the face of The New Deal, and this film celebrates that. The film ends with a parade, with people wearing every uniform you can imagine. Re-employed workers parading through the streets. Shirley Temple is conspicuous in marching. We see her face in close up.

The film was not itself a huge moneymaker. It had mixed reviews. But there was no negative review of Shirley Temple in that film.

Shirley’s relationship with African American actors was actually rather revolutionary at the time. How is her collaboration with black actors historically significant?

African Americans are restricted in mainstream films. There were very few roles for them. The actor who she is most prominently linked with is Bill “Bojangles” Robinson, in two films in 1935, The Little Colonel and The Littlest Rebel. He was, by her account, her favorite dancing partner. He plays servant roles in his films with her. The films preserve the racial etiquette of the period. His dancing is quite magnificent and he is very popular among white audiences. These films played very well in the white South. He was seen as a major star among African-Americans. Even in the film credits, his name comes at the end. He is not given the billing of a co-star.

What was Shirley Temple like, post-child-actor era?

She wrote an autobiography called Child Star, published after her parents died, in 1988. It’s dedicated to her mother. Its last words were “Thanks, Mom.”

She recalls [her career] with some affection. Although in that book, there are moments of bitterness. This includes the discovery that, of the millions of dollars she made, only $47,000 was preserved in the bank as of 1950.

Her first marriage, which she entered at age 17, was, by her own account, a disaster. She had one daughter in that first marriage, and then remarried, to Charles Black, when she was 22, and had two more children with him. They had a long and happy marriage.

She was involved in various charities and sat on various corporate boards. She ran for Congressional seats in California in the Sixties. She was not successful in the Republican primary, but did serve a number of diplomatic posts, including the Ambassador to Ghana under Gerald Ford, and the Ambassador to Czechoslovakia under George Bush.

She was, by all accounts, a person who did not look back, but would be gracious when people would speak about her career. She was simply a woman who did not want to live a life with her scrapbooks and stay in the shadows. She was very much engaged in the current world, the global world.

Dig it if you can:

Into bed you’ll hop with this sweet Shirley stuff: