With The Great Funk, we sniff at the decade that gets no respect. And yet, try as we may, we still can’t shake its booty.

As Lou Grant once said on The Mary Tyler Moore Show, “I hate nostalgia. I hated it then. I hate it now.”

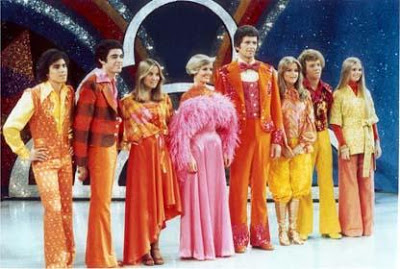

The Seventies, though, linger on like a macabre dream that haunts your ordinary day. Those who have lived through those years will admit that it all may not have been as bad as it seemed; those who were yet to be born now see it as a bitchin’ night of the living dead, but in a good way, with the dead walking that way because their jeans were so tight.

Whether experiencing it first hand or by cultural memory, they happened. Oh boy, did they happen. And we’re still trying to figure out why.

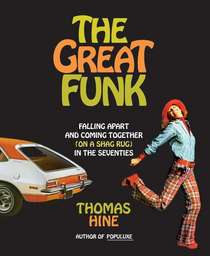

The “why” is where we must leave it to Thomas Hine. He’s the former Philadelphia Inquirer art and design critic, and he sees what we see, only deeper and more profoundly. He has taken a look at the Me Decade with X-Ray glasses, and sums it all up brilliantly in his book, The Great Funk [Sarah Crichton Books].

Loaded with authentic pictures that will make your mouth drop open (the living rooms! The Afros! The Ford Pinto!), The Great Funk shows us exactly where we skidded off track, and how far those skid marks could be measured (pretty darn far, it turns out).

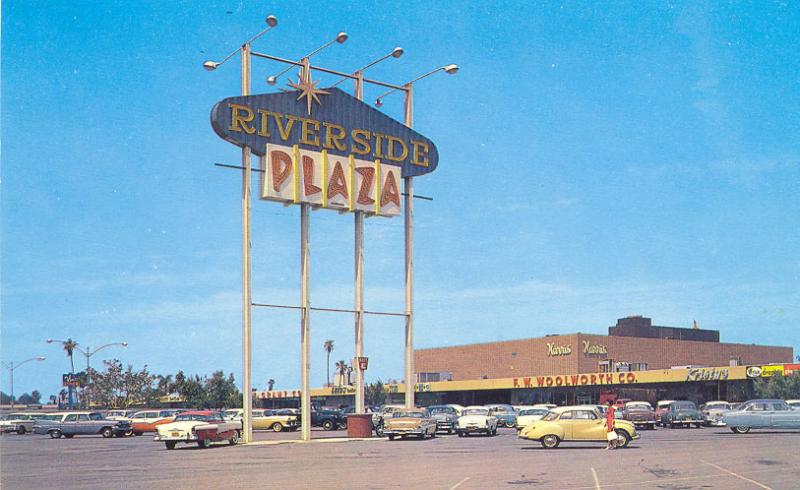

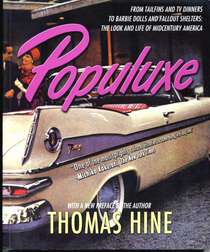

One of Hines’ earlier books, Populuxe, is now considered a classic look at the design and cultural mindset of a happy but regimented postwar America (the tailfins! The Jetsons! The ashtrays! And yes, once again, the living rooms!).

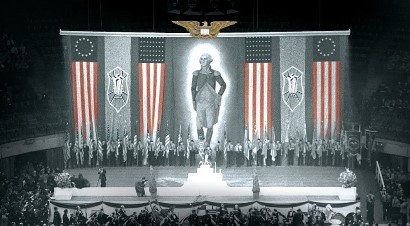

During the Populuxe era, our minds were shaped and brainwashed by advertising agencies (think Mad Men). We had total faith in our government, in our military, and in science and technology. By The Seventies, this blind trust had totally disintegrated. As a result, the culture splintered and the splinters didn’t tickle.

Here, we talk to The Man himself, as he explains how we all tried to get over.

What is the significance of the book’s title?

The Great Funk is meant to be a description for the decade of The Seventies, which was actually a little bit longer than the decade itself, starting in late ‘68 and ending on Inauguration Day of 1981.

Of course, it’s a play on the term The Great Depression. Somehow, what happened wasn’t exactly a depression, but it sure was a funk. It’s also a play on [The Seventies’ rock band] The Grand Funk Railroad.

The reason that I like the word “funk” is that it includes both the negative and the positive. People were seeking out the funk during The Seventies; they were seeking out the music.

Funk also has a kind of connotation of being old and smelly and dirty. It also relates to authenticity. People were looking for things that had texture and age, that seemed real.

We were coming out of the period of almost blind belief in technological progress. [We had previously believed that] everything was going to get smoother, shinier, more metallic or more plastic. We were heading into a Jetsons age, but instead we ended up in a time with lots of texture and houseplants and things rescued from the garbage pile and the attic. Instead of going headlong into the future, we were maybe salvaging some of our past, and allowing that to be a basis for thinking about all sorts of futures.

How is The Great Funk a natural outgrowth of your classic book on Fifties-era design and mindset, Populuxe?

Even when I was writing Populuxe, I had thought that the book that would grow from Populuxe would not be about the 1960s, which was already so chewed over at that point.

1970s fashions and tastes were bizarre in wholly different ways than The Fifties were. It was a period in which the whole culture of Populuxe became unraveled.

The national memory of The Seventies is a unified “ick.” We all have a good time looking down on the Seventies. Is that fair?

I think The Seventies are funny. And I think when we look back at any time period, certain things are funny.

With a little bit of distance, you start to understand what was going through our heads at that moment. One reason that I wrote about The Seventies at this time is I believe a number of the issues that arose in The Seventies – shortages of oil, issues of global warming and so forth – are back with us.

To a certain degree, we are getting more of a backlash against “clean and modern,” and getting more into a sheltering time. Even a lot of fashions from The Seventies – not the most outrageous ones – but a lot of them are coming back.

We’re not as focused on not repeating The Seventies. We’re not as focused on rejecting The Seventies as we were, say, five years ago.

What was most apparent to you about The Great Funk?

Ideologies that people had held onto for long periods of time were just crumbling to bits.

There is not just one kind of progress. There is not just one kind of way of living your life. You can choose the way you want to live your life. You could choose your telephone, and you could choose many aspects of your lifestyle.

Women could live alone. Women could choose to have children without being married. You could choose to live with somebody of the same sex. There were all kinds of choices that hadn’t been admitted. They certainly were happening, but they hadn’t been admitted. They were not part of the vision of progress that was [previously] being presented by advertising and the media.

Could The Seventies have been different?

Mistakes were made. What I am most interested in is what happened and to figure out some explanations.

The Great Funk examines both failure and possibility, and how the two often relate to and negate each other.

The basic premise of the book is that people understood that there had been failure in the system, failure in everything they expected to happen. So they began to say, okay, there are other possibilities. And with some of these other possibilities, it is sometimes difficult to distinguish the positive from the negative.

On the one hand, you have hippies going away to colonies in the mountains and trying to live a pastoral fantasy. On the other hand, you have people going out to the mountains with guns and being survivalists. It’s hard to make the distinction: the hippie or the Unibomber. They are both coming out of this same mentality.

Likewise, the gay movement happened, and it also unleashed a new wave of religious fundamentalism.

The postwar consensus was corporate, based on big government, big labor, very much molded by advertising agencies. What happened is when liberalism failed, people went into all kinds of directions. The way in which things fell apart in that period is still an issue that is with us.

Let’s talk about some of the icons of the age, like the AMC Gremlin…

It was desperate. I kind of like it. They had problems, apparently. It did not occur to me to buy one.

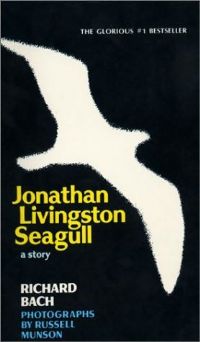

[The novel that caused a cultural sensation] Jonathan Livingston Seagull

One of the best-selling books of the period. It’s all about leaving the flock and forming your own flock. A proto-New Age type. There are those who aren’t totally stupid who swear by it. It’s still a fairly popular middle-school book. It’s slightly subversive: if the only reason you’re flying is for food, then there is no reason to fly. Yet that was clearly the message that I grew up with, that you trade off choice for prosperity.

Hair and the love for hair (Farrah Fawcett, John Travolta, blow dryers, hairy chests, Gee Your Hair Smells Terrific!)

That’s related to when I was talking about funk. It’s about authenticity. It comes out of your body. It’s really from you. In the sixties, it had become a real way of rebelling. But what happened in The Seventies, people who weren’t rebelling against anything took it as a fashion opportunity.

That’s related to when I was talking about funk. It’s about authenticity. It comes out of your body. It’s really from you. In the sixties, it had become a real way of rebelling. But what happened in The Seventies, people who weren’t rebelling against anything took it as a fashion opportunity.

The need to be “authentic” versus the popularity of polyester:

Polyester is remembered for the moment when people got sick of it, even though it had been around for a lot longer than that.

I talk about an artificial slate that comes with the promise: it looks so real, it’s unreal. That seems to me to be a characteristic statement. People want authenticity, but even more than that, they want intensity. People are always doing contradictory things.

The birth of the computer culture

The computer culture did not come into its own until later, but the values of the computer culture were very much Seventies values: being able to do things on my own, to have my own tools, to not depend on IBM or anybody big to tell me how I have to live my life and use tools.

The rise of cubicle culture in corporate America

One of the issues that created economic problems in The Seventies was the difficulty that the economy had with accommodating both the largest generation of new workers in American history [the baby boomers], and also the changing expectations of women, that they would in fact work through what people viewed as their prime child-bearing years.

The cubicle culture made possible this accommodation by tearing apart hierarchy, by taking away the idea of “the name on the door.”

You put people in cubicles, and you change the nature of business, and you downgrade employees without doing so directly. What this does, in an indirect way, is allow women to be in more responsible positions, even though what it did was make the whole process of working in an office less pleasant.

Except maybe for Archie Bunker, most people didn’t want to go back to the way things were, even as bad as things had gotten!

We did have this engrained thing that whatever happens has to be called progress. There probably were people who wanted to go back. I know I wouldn’t have.

In a way, that’s the bottom line of the book, that for good and for ill, this is when the Populuxe era unraveled and when it deserved to unravel, because it wasn’t sustainable. It wasn’t sustainable because of the state of the world.

When exactly did The Seventies end (or did they?)

Precisely saying when The Seventies started was tough, but it’s really easy to say when they ended: when Ronald Reagan was inaugurated and, simultaneously, the American hostages in Iran were released.

The period [of The Seventies] had just been too traumatic. On one hand, it offered some space for freedom and experimentation, and on the other hand, it shook people’s sense of the way things should be.

Reagan had literally been a spokesman for progress [for TV commercials for General Electric: “Progress is our most important product.”].

He came along promising that we could make progress again and that we can go back to “normal” life in America; it was a very attractive thing. I suspect that even without the hostage crisis, Reagan would have won in 1980.

Why did it take you so long to write this book, twenty-one years after the publication of Populuxe?

It turned out that it was worth waiting to do this book, because it provided a perspective.

There is a cycle of nostalgia: ten years later, people start looking at the music again.

Twenty years later, there comes a show like Happy Days or That ’70s Show, where some of the styles are brought out, partly to laugh at and partly to feel nostalgic about.

Ten years later, you start to get the feeling of “what was this all about?” Certain things were really good and really worth looking at.

You want funk? Here’s your funk:

Do you have funky ’70s memories? Kindly comment below!