Over here, World War I vets recall the Great War, while we learn about life at age 100.

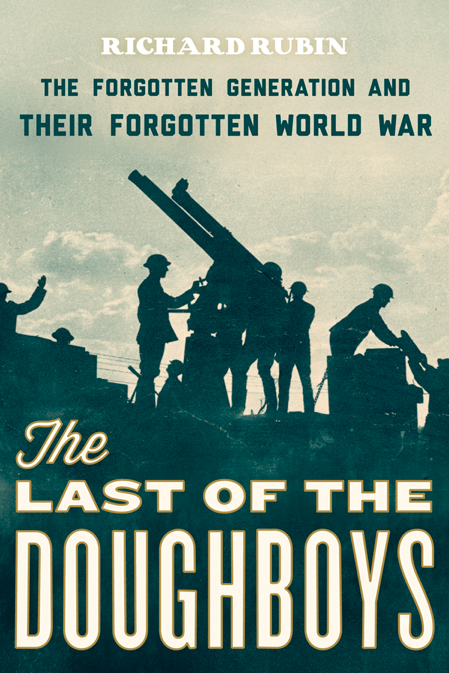

World War II gave us The Greatest Generation, but poor, old, mostly forgotten World War I has yet to earn its props. Until now.

Journalist Richard Rubin has written a historical account of what was then known as The Great War (in 1918, it would have freaked people out to give World War I a number!).

What sets this book apart from other World War I histories: it’s told firsthand, by those who lived it. That’s right. America’s oldest veterans give the author an up-close-and-personal account of their experiences in the trenches in 1918, all told in the 21st century.

The horror is still fresh: mustard gas, muddy trenches, French whores, lice and rats are par for the course; a constant bombardment of shells, bombs and low-flying aeroplanes, along with patriotic songs, endless corpses, and the even more lethal Spanish Influenza play into the memories as well. All stories are told from modern living rooms and nursing homes.

The Last of the Doughboys relies on the surprisingly strong and mostly crystal-clear memories of the young soldiers who dug in and fought for liberty, freed France from the Hun, and lived to tell about it (and then some).

The added value to this experience is learning about people who are 100 years old and over. We learn that living past 100 takes more than just avoiding cholesterol, and that not all people this old are without their sensibilities and humor.

Let’s face it. If they weren’t over there, we wouldn’t be here.

In our Modern interview, Rubin tells us what it’s like to talk to 100-plus-year-old veterans who studied a horrendous war up close.

World War II is still very much with the culture, but World War I seems to have faded from view. Yet that war is hugely significant in our history.

In Canada, that’s not the case, but in the United States, we have largely forgotten the war. America played a great role in the war and it would have ended differently had we not entered it.

What was it like to talk to people who are 100-years old or older?

I had never known anybody that old before I started doing this. I’ve known people in their 80s and even their 90s. Their memories were pretty frail. I just assumed that progression [would continue].

What I hadn’t understood is that people of that age are different from the rest of us. People who are capable of living to be that old are genetically different. They age more slowly than the rest of us do. They are less susceptible to things that take a lot of us down, like Alzheimer’s disease and dementia.

Did you feel that their memories were reliable?

When you get to be that age, memory works differently. We tend to think that our most vivid memories are things that had happened to us most recently, and as time passes, they fade. But at that age, memory is a matter of “first in, last out.” So they can remember very clearly things that they had done that long ago but often cannot remember what they had for breakfast.

What is it exactly that makes these people different from most people?

I think that they were really engaged people, for one thing. I don’t think they were the kind of people who kept their noses down. I think they were people who were aware of what was going on around them.

You have to remember that during World War I, they didn’t start drafting people until they were 21 years old, so most of the people I interviewed were not that old. They volunteered.

One of them told me that he was out of a job and needed the work.

A lot of them – maybe most of them – came from very small towns. Their childhoods and young adulthoods were things that we have difficulty imagining today. They grew up without electricity or automobiles. Most of them may have never left the county in which they had been born.

A lot of them – maybe most of them – came from very small towns. Their childhoods and young adulthoods were things that we have difficulty imagining today. They grew up without electricity or automobiles. Most of them may have never left the county in which they had been born.

On one hand, their expectations were very modest. A great many of them lost their fathers at a very young age. They expected that their life was going to be hard. But they also saw the war as a chance to get out of the life they had imagined for themselves.

Were people back then more naïve than they are now? Was it easier to feed them patriotic propaganda? Were they not as savvy to media manipulation?

That depends on conditions and circumstances. People back then were pretty sophisticated in some ways also. These are people who often read two or three newspapers a day. In your average American city, they probably had a half a dozen newspapers to choose from. These were, in many ways, very informed people.

I wouldn’t say that they were any more gullible than we are today. The war came along, and almost overnight, it became unacceptable to spread anti-war views. You could go to jail for speaking out against the war. That is something that hopefully would not be possible today.

The German Kaiser was an easy target. He was easy for Americans to hate.

Oh, he certainly was. Just look at the man. He had that mustache that shot up at the ends. He was somebody who was very easy to caricature. Put that spiked helmet on his head and you had a ready-made monster to hate. He did a great service for propagandists and songwriters also.

Every generation thinks they have invented sex, but sex was a great temptation during this war. What went down, so to speak?

The men and women I had interviewed were reluctant to talk about it. Venereal disease was a terrible problem during that war and the Army did all kinds of things to combat it, knowing that soldiers are going to do what soldiers do. [Military advice included:] “If you absolutely must, use a prophylactic.” And I don’t know how well that message got out, because there were very large incidents of venereal disease in that war.

World War I was the war famous for its muddy trenches, filled with lice, rats and corpses. It must have been pure hell.

All I have to say about it is this: it’s never happened since. If something about war is so awful that all sides agree, ‘we are never going to do that again,’ you have to figure it’s terrible. These trenches were very muddy. The water table in France was not very deep, and it rained a lot.

The Germans often built their trenches with concrete. But the Allies were forbidden to do this, because it was considered to be bad for morale. If you built concrete trenches, it means that you were staying for a while. And we were always supposed to be moving forward to push the Germans out of France.

Many of the German soldiers were actually friendly toward the Americans.

There were a lot of stories of captured German POWs speaking in perfect, unaccented American English. The captors would ask how this is possible, and the captors would [answer]: “Well, I lived in America for eight years. I was a waiter in Chicago or Coney Island.”

It was a time when there was a lot of trans-oceanic work going on. [A lot of Germans] had a great fondness for America. They didn’t particularly care to fight Americans.

The war was relatively short, but the deaths and casualties were astronomical.

America entered the war on April 6, 1917. The war had already been going on at that point for two years. The first American deaths happened around November 1917, and the war was over exactly 12 months later. So it was only 12 months of combat for Americans, but in those 12 months, America lost 117,000 men.

The veterans did not have an easy time of it coming home. How did they survive?

You have to remember that when these guys came home, there was no GI Bill of Rights. When they came home, their stores were closed because there was no one to work there. Their farms were ruined because there was no one to run the farms. There were no government programs in place to assist them.

There was a movement to get some help for these veterans. It faced a lot of opposition in Washington. What was eventually passed was a one-time payment, but not until 1945.

So a few years later, the Depression hits and the veterans needed that money then! They petitioned Washington for it, and the President at that point, Herbert Hoover, said, ‘sorry, we can’t afford it.’

In 1932, a spontaneous movement arose, where veterans started gathering and progressing toward Washington. They set up camp there, and it was entirely non-violent. There were strict rules against any kind of radical talk among these veterans, and the rules were set by the veterans themselves. They didn’t want to come across as radicals. They just wanted what they felt was due them and what they needed very badly at that point.

The veterans of every war after that at least had the GI Bill in place.

Were you tempted to ask the surviving veterans about their secret to longevity?

One thing I asked everybody I interviewed was, ‘what is the secret to your longevity?’ I got a lot of handy tips. But people I’ve interviewed were some of the most remarkable people that I’ve ever met. I would say that knowing them has really made me a fuller person, even though I didn’t spend all that much time with most of them.

I asked one of them, ‘what’s it like to be 106 years old?’ And he said, ‘it’s no different to me than being your age is to you.’ That was a perspective I’ve never considered before.

Experience this awesome book here.